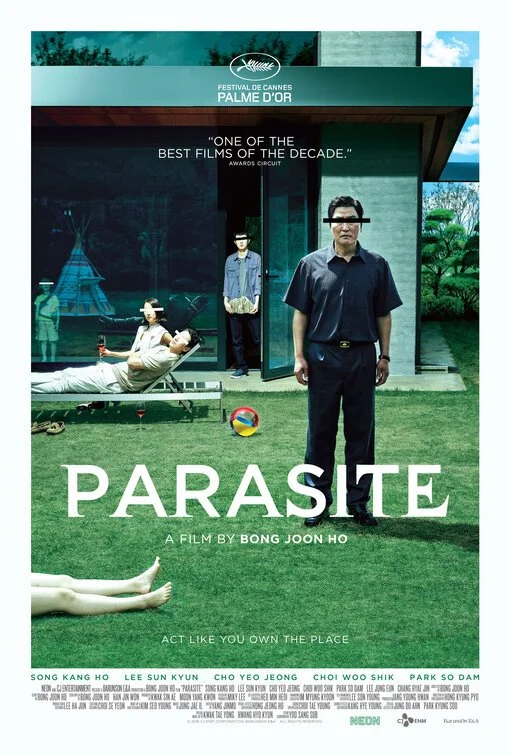

Parasite: A Masterclass in Worldbuilding

/Using what we’ve learned from food and society in worldbuilding, let’s take a look at some of the writing decisions that make Bon Joon Ho’s 2019 film Parasite so successful in immersing us in its world. I should warn you; I’ll be giving heavy spoilers for this movie. If you haven’t seen it and want to, I recommend doing that before reading this article! Trust me, it’s worth it.

Parasite is set in our world—that is, contemporary Korean society. Of course, most of us know what it’s like to exist in the world and won’t have any trouble decoding the world of the film. With that said, everything audiences need to know about society and the people in it are conveyed to us through either dialogue or visual storytelling. Forgetting what we know about reality, let’s examine the world of Parasite.

Society

The world of Parasite is populated by the haves and have-nots of society. The movie opens in the semi-basement home of the Kim family, with the first words spoken being “We’re screwed. No more free Wi-Fi.” Not only does this set the tone for the movie, but it also communicates to the audience that the protagonists are firmly a part of the societal have-nots.

This is a family used to pulling together to make it through life. A family that’s accustomed to using their wits to survive.

Class and Hierarchy

The film makes it clear that one of the great separators in this society is education, as evidenced by a friend (Min-hyuk) of the Kim’s son (Ki-woo), who pays a visit. As a post-secondary student, Min-hyuk is almost revered by the Kim’s. He is a young man in a position to better himself—someone with possibilities in their future.

When Min-hyuk arrives, the family scrambles to make room for him at their table, where he gifts them a decorative rock “said to bring material wealth”—a recurring totem in the film.

The Kim’s are showing deference and respect to someone they perceive as in a better position, both financially and socially. A sharp contrast to their later depiction of the Park family.

The Parks

The Park’s are a young and affluent family. Instead of living in a dank, bug-infested semi-basement they live in a large, naturally bright, gated house. They have a housekeeper and driver. Freshly cut plates of fruit that are made for them. They hire tutors for their children.

It’s precisely this reliance on hired help that allows the Kim’s to worm their way into their household staff. Beginning with a recommendation from Min-hyuk to tutor the Park’s daughter, Ki-woo then recommends his sister as an art tutor for the son; Who then recommends her father as personal driver; Who then recommends his wife as housekeeper.

The “Belt of Trust”

The Kim’s work together to tightly plan, coordinate, and execute this elaborate scheme. This “belt of trust”, according to Mrs. Park, illustrates both her families naivete and reliance on social currency to navigate life. The Kim’s understand this and do not hesitate to exploit it.

Similarly, when handed a business card made by the Kim’s for a fake service company, Mr. Park comments that “You can tell from the card they’re high-class. Cool design.” Coming from a world of status symbols and classist perceptions of wealth, Mr. Park relies on the superficial to inform him in his choices.

A Lot Happens (Seriously, Watch the Film)

Ultimately, things do not end well for either family. The Park’s are mentally scarred by the end of the film (the husband physically, too). The Kim’s daughter is killed. Ki-woo and Mrs. Kim—after Ki-woo receives life-saving brain surgery from being bludgeoned by the man in the basement—are prosecuted. Mr. Kim retreats to the basement of the Park’s house, becoming the next parasite.

Right?

So, just who’s the parasite here?

Parasite explores themes of class and wealth disparity, among others. While it’s easy to argue the man in the Park’s basement, and subsequently Mr. Kim, are the parasites, the depiction of the Park’s, their wealth, and lifestyle point to another.

There’s no question the Kim’s hustle. Constantly. Whether folding pizza boxes, delivering fliers, or finessing the Park’s, they’re working. The Park’s, for all their wealth, are never shown doing anything but relaxing, worrying about non-issues, gossiping, or giving orders to their staff.

Even after Ki-woo and Mrs. Kim are prosecuted they don’t stop. They can’t stop. Not if they want to eat. Ki-woo says, “Those detectives still wore themselves out tailing us.”

I ask you then, watch the movie for yourself. Use what you know about worldbuilding to dissect the world of the film, and with a critical eye ask yourself: who adds more value to society? Then take a look outside and ask the same question.

Melanie Pledger is a second-year student of Professional Writing at Algonquin College in Ottawa, Ontario. She is published in Heritage Matters magazine and has done extensive research on local soldiers from her hometown, Owen Sound, where she created a museum exhibit in 2015. Melanie received the Lieutenant Governor’s Ontario Heritage Award for Youth Achievement the same year. Melanie lives on the water where she enjoys swimming and paddle boarding—weather permitting, of course.