Worldbuilding and Meta-Narrative in a Ghost Story

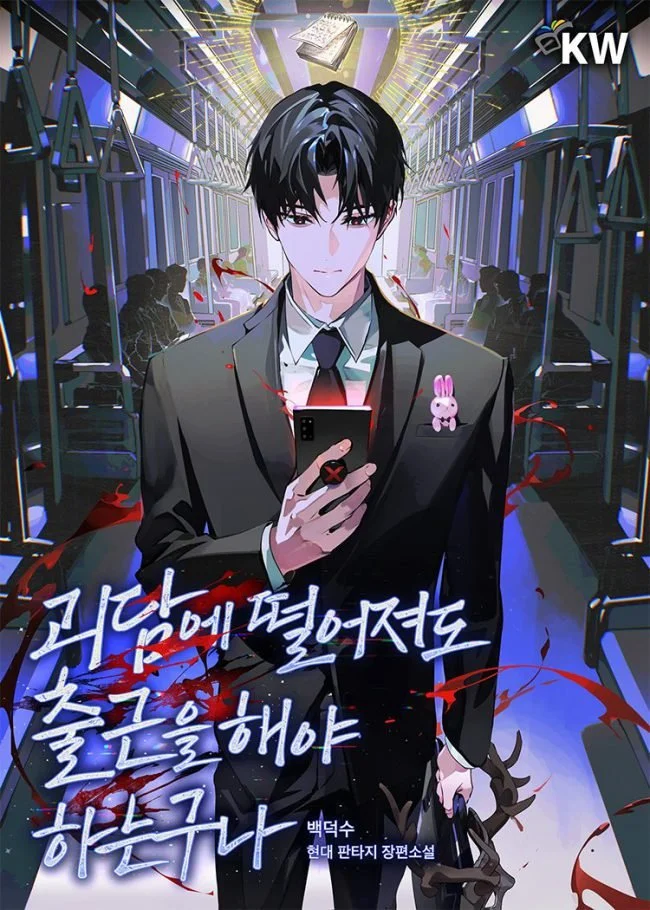

/While worldbuilding is often discussed in the context of blockbuster Western media, great compelling worlds are built everywhere. For my case study, I’ve chosen the web novel Got Dropped in a Ghost Story, Still Gotta Work by Baek Deoksu (백덕수) to demonstrate that good worldbuilding goes beyond language, platform and popularity. This allows me to examine the principles of worldbuilding discussed previously in this blog in a fresh context.

For the purposes of this post, I’ll refer to both the fandom wiki and the translated novel, which will contain spoilers.

The setting, the language

The protagonist gets transmigrated into a world similar to his own, with one glaring difference: ghost stories exist. Whether they sustain themselves or are manifested into existence, they are very real, and so are their consequences.

Despite the setting of a modern-day Korea, the worldbuilding shines through its three major groups focused on for most of the story: Daydream Inc., the Supernatural Disaster Management Bureau, and the Nameless Church.

These groups use different terminologies to call ghost stories. Daydream calls them “Darknesses,” the Agency calls them “Disasters,” and the Church calls them “Powers.” All of these terminologies are linked to their differing views on the ghost stories

It wouldn’t make sense for the Bureau to call ghost stories “Powers” when they mostly have a negative view on them, since ghost stories often pose danger to civilians. Alternatively, the Church calling ghost stories “Disasters” doesn’t fit either because they worship them.

Unveiling the story mechanics

The story doesn’t just use language and its setting to its advantage, but also the two-layer rule. For example:

Why do people risk their lives at Daydream Inc?

It’s to get the Wish Ticket.

Why do they want the Wish Ticket?

The Wish Ticket allows their wishes to come true. It can’t change the world, but it can grant personal wishes with absolute power.

Where does the Wish Ticket come from?

It’s created by the dream solution, which requires the dream essence collected by the employees who go through ghost stories.

The background that adds dimension

Outside the main cast, the background characters’ very existence contributes to the world in significant ways. Whether they are the Daydream employees killed in the orientation test Welcome to Abyss Transpo ghost story because they didn’t participate enough, or those sent to teams beginning with X, Y or Z, becoming designated sacrifices for the elite teams, the background characters have a notable value.

They demonstrate that this world is unforgiving to regular people, which grounds the story. Not everyone has the advantages the protagonist has, and not everyone has the kind of personality or the morality to make it in this world.

Plus, having unnamed characters contributes to the meta narrative of the in-story wiki. It requires “irrelevant” characters to die or go missing or have misfortune happening to them to add weight to the written ghost stories.

If they didn’t exist, most of the appeal of those stories wouldn’t exist either—the only existing records would be the ones featuring the named characters, who often live, and there’s nothing scary about a story when you only learn about those who’ve survived it.

The Nameless Religion, made from unnamed characters, formed a cult after reading scriptures (parts of the wiki). They are under the belief that through causing themselves the most pain and extending it as long as possible, they will become a meaningful being (a named character) and will be chosen by their god and will live forever.

Their god is “Ireum-nim” which translates to Name, and are the anonymous authors who wrote the wiki. It’s these kinds of functions the background characters have that enrich this world beyond being a simple story.

Conclusion

This case study demonstrates the versatile usage of these worldbuilding techniques in one narrative, all of which allow the world to become more believable and fun to engage with. While the narrative is ongoing, the author's consistent payoff of long-standing mysteries suggests a thoughtfully planned world that will likely continue to develop in a cohesive and satisfying manner. The strength of its worldbuilding proves that a story's impact is defined by skill and not its origin or popularity.

Marion Landry studies at Algonquin College in the Professional Writing program. She began writing personal stories for about six years and has developed a critical sense of storytelling. Her favourite genre is fantasy, as are most of her stories-all filled with in-depth worldbuilding and richly explored narratives.