Grit, Glory & Girlhood: Toni Morrison and the Truth of Womanhood

/Growing up, like many other women, I was taught that to be a woman is to be soft, graceful, and quiet: to speak gently, to move carefully, and to avoid taking up too much space. Toni Morrison’s work challenges these stereotypes and expectations by capturing the realities of womanhood through writing about women who are raw, imperfect, and real. They are not saints nor victims, but human.

Her stories reveal how race and gender are deeply intertwined and continuously impact how women of colour experience womanhood, making her work a cornerstone of intersectional feminism long before Kimberlé Crenshaw officially coined the term “intersectionality” in 1989.

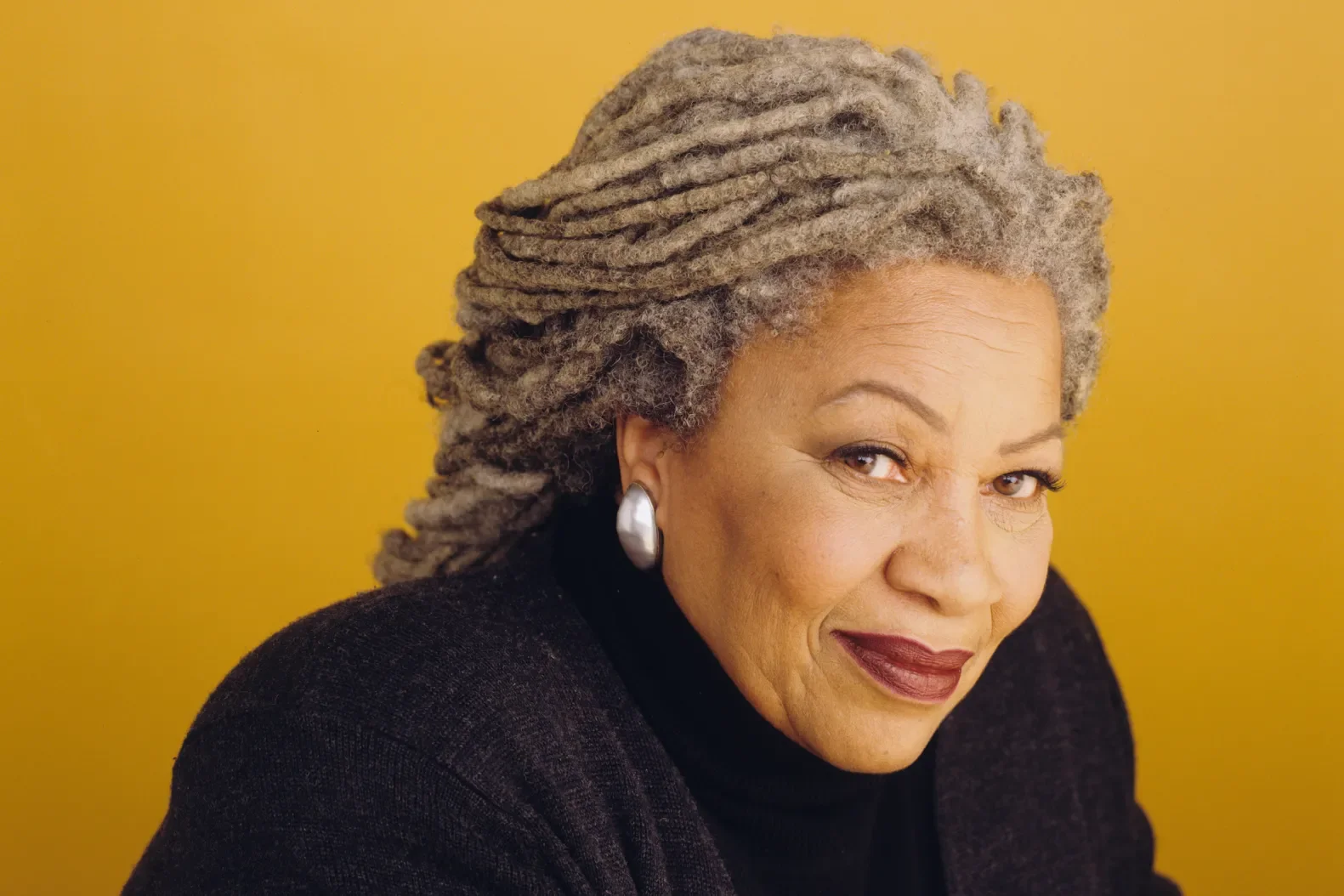

Picture Of toni morrison by timothy greenfield-sanders

A Feminist Icon: Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison is one of the most influential modern feminist writers. Born on February 18, 1931, in Lorain, Ohio, Morrison gained interest in writing by becoming an avid reader. As outlined in this article, throughout her life, she experienced racial segregation and saw how racial hierarchy divided people of color based on their skin tone. Through her portrayals of Black womanhood, Morrison highlights how growing up as a woman, and especially growing up as a woman of colour, demands both strength and softness in a world that punishes both.

Where Race and Gender Intertwine

Morrison’s fiction aimed to reshape how readers see women, identity, and power. Her perspective was revolutionary because she centered Black women at a time when literature rarely did. Her novels, The Bluest Eye (1970), Sula (1973), and Beloved (1987), explore the places where race and gender intertwine, creating complex identities for her characters. As one critical analysis puts it, Morrison’s exploration of intersectionality “delves into the unique challenges faced by African American women” and reveals that their experiences “cannot be neatly separated into categories of either race or gender.” Morrison’s characters show how these forces overlap to shape every part of their lives, from their bodies and minds to their relationships with themselves, society and others.

In The Bluest Eye, Morrison introduces a character named Pecola Breedlove, a young girl who prays for blue eyes so she can finally be seen as beautiful, a word she associates with whiteness. This wish highlights how racism and sexism work together through culture to destroy the self worth of young Black girls long before they get a chance to learn how to love themselves.

Beloved (1987) explores the dark aftermath of slavery through her character Sethe, a mother who makes an unthinkable choice: killing her own child rather than seeing her re-enslaved. As one scholar explains, Morrison’s characters “grapple with the legacy of slavery, the impact of racial discrimination, and the pursuit of identity in an environment that seeks to dehumanize and silence them.” Morrisson encourages her readers to look directly at what society often refuses to see. Her characters are women caught in overlapping systems of oppression, struggling to define themselves against a world that insists on defining them first; they highlight why intersectional feminism is important. Her novels reminds us that womanhood is not a single, shared experience. It is layered with culture, history, and pain. For her, to write about women was to reclaim a narrative that had long been told through a white, male gaze. Her fiction challenges readers to confront the systems that shape not only how women are seen, but how they see themselves.

The Enduring Power of Morrison’s Feminism

Before the term “intersectionality” was coined, Morrison was already writing it into existence. Her characters live at the crossroads of race, gender, and history, and highlight how these impact their identities. In a 1994 Time interview, she reflected on her role as a writer: “I felt I represented a whole world of women who either were silenced or who had never received the imprimatur of the established literary world.” Representation is what makes Morrison’s work essential to feminist thought today. Her stories still challenge readers to see women (especially those of colour) as full, complex beings.

Deborah Feingold/Corbis via Getty Images

Évangéline Doucet is a professional translator turned writer, currently completing her final year in the Professional Writing program at Algonquin College where she has focused on honing her skills in editing, research, and digital communication. She is also a member of WordTonic, a global writing community where she is building her copywriting portfolio. When she’s not freelancing or studying, you can usually find her drafting essays and reflections on Substack, often inspired by literature, culture, and politics.