Posted from the Past

/Fighting the War of Words

In a conflict like the First World War, deadlier than any that had come before it, much of the public discourse surrounding the war concerned the new methods of waging war that the conflict introduced. Weaopns like the machine gun, mustard gas, the trench gun, serrated bayonets, and the flamethrower brought on accusations of wartime atrocities from both sides. In the press, the war was framed as a battle between the civilized and the uncivilized, with both the Allied Powers and the Central Powers claiming they were the former. The propaganda machines on both sides got to work early in the war in painting their enemies as barbarians.

Postcards were one of the most popular ways to circulate propaganda during the war, and much of the propaganda produced by both the Allied Powers and the Central Powers was intended to demonize the enemy through racial stereotyping. Since the Central Powers were by and large the ones occupying territory, accusation of Allied atrocities wouldn’t work. Instead, they took aim at the Allies’ numerous colonies. Germany, though its leaders desired colonial expansion for the latter half of the 19th century, held far less territory than the French or the British. German postcards the one to the right derided their enemies for their close association with what many Europeans considered inferior people. The caption reads, “Old England, the culture propagator among his employees.”

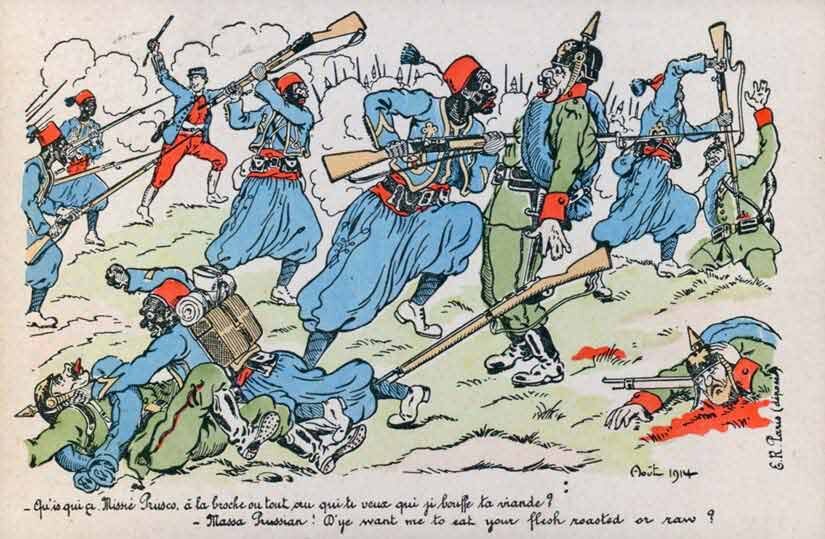

Germany frequently used its enemies’ colonies against them, despite desiring those colonies for itself, framing the war as a battle between civilized Europeans and barbaric African colonial troops. Much of their focus was on French troops from their colonies in Senegal, depicting them as savage fighters. French propaganda responded in turn, but not in the way you’d expect. Rather than defend their soldiers from the racist barbs of their enemies, French propaganda used the barbaric image the German’s had created against them, suggesting that if these barbarians were superior in battle to the Germans, the Germans must fall below them on the racial hierarchy.

Other Allied postcards, reinforcing their position as the civilized party in the war, accused the Central Powers of aggressive militarism. As the leader of the Empire, Kaiser Wilhelm II was a common subject of this type of postcard. The postcard to the right was made in Italy, shortly before they joined the Allied Powers, and reinterprets Germany’s aggression as the Kaiser’s hunger to devour the world. Notice the exaggerated features of the Kaiser; caricature was key to crafting images that were immediately recognizable to viewers, and the Kaiser was known for his moustache.

Anti-German sentiment was so high among the Allied nations that anything associated with Germany was shunned completely. A notable Canadian example is the renaming of Berlin, Ontario, to Kitchener, after the British War Secretary. This sentiment made its way into postcards like the one to the left, rejecting the Dachshund, simply for being a breed of dog with a German name.

The First World War was one of the first and greatest examples of total war, in which battles are fought not only on the battlefield, but in the mind of the public. A key weapon in this fight was the postcard, and ones like those previously mentioned played a huge role in reinforcing the platforms and goals of both sides in the minds of their citizens.

Alex Foster-Petrocco

Alex has a BA in History from Carleton and is currently a 2nd-year Professional Writing student at Algonquin.

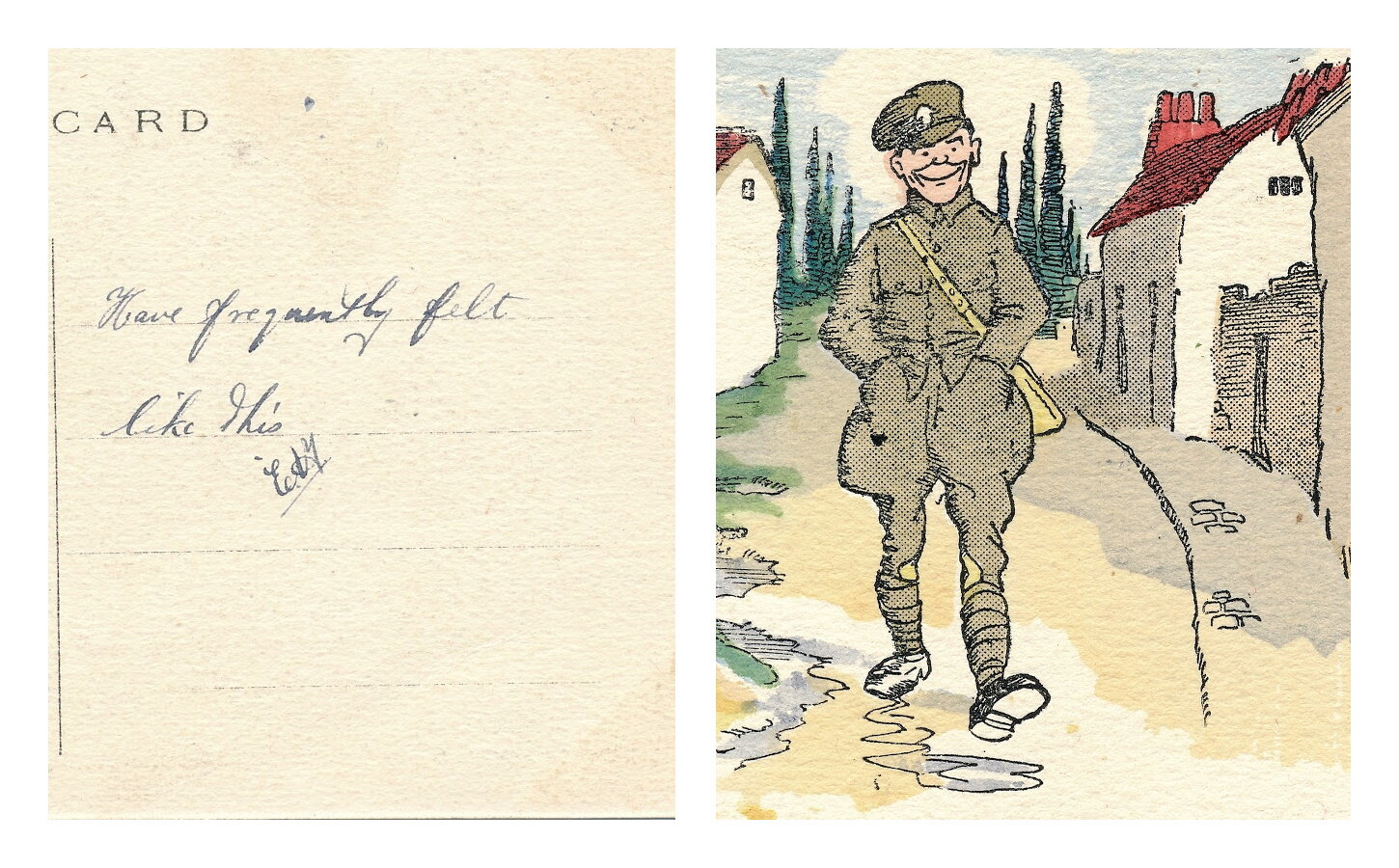

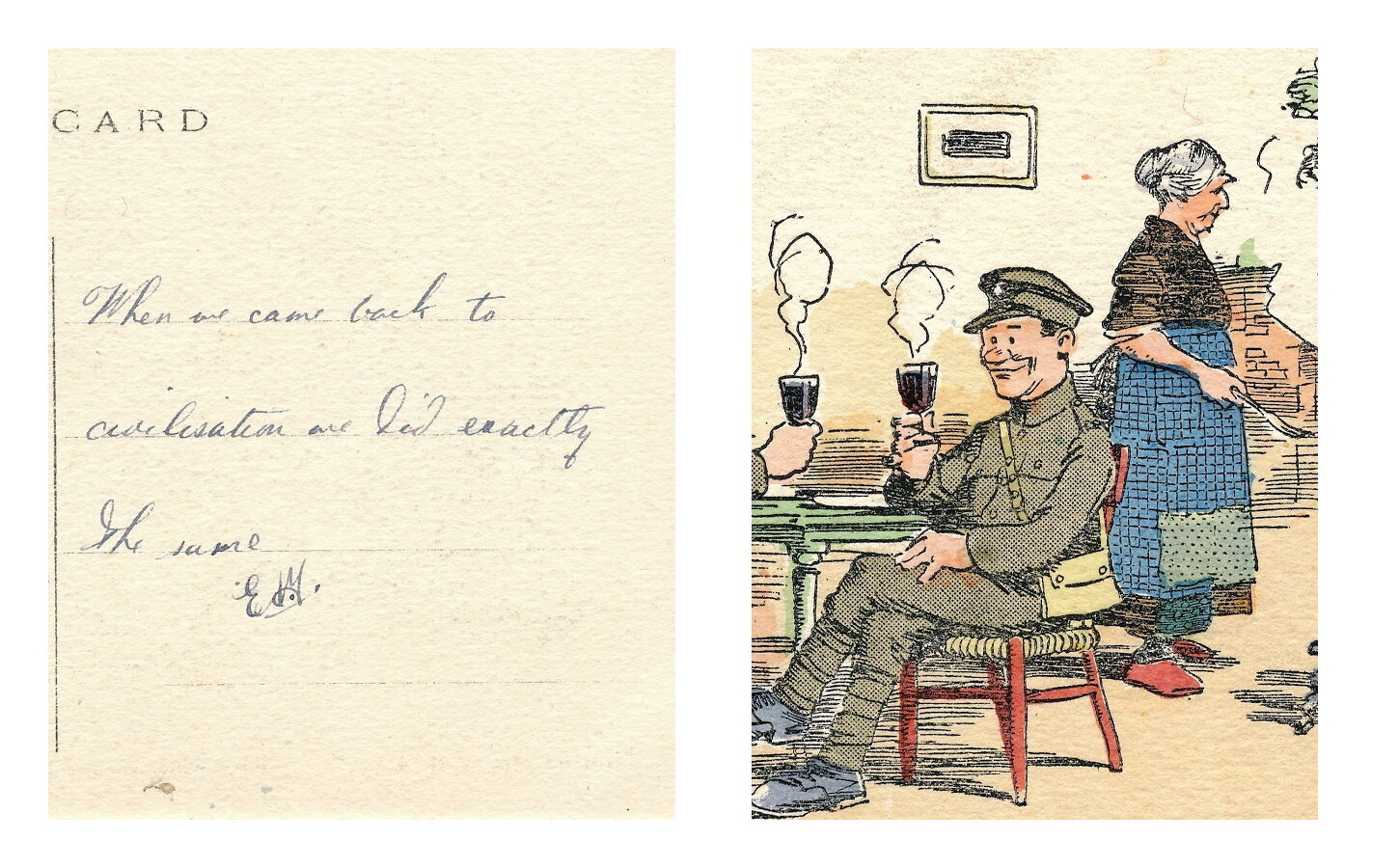

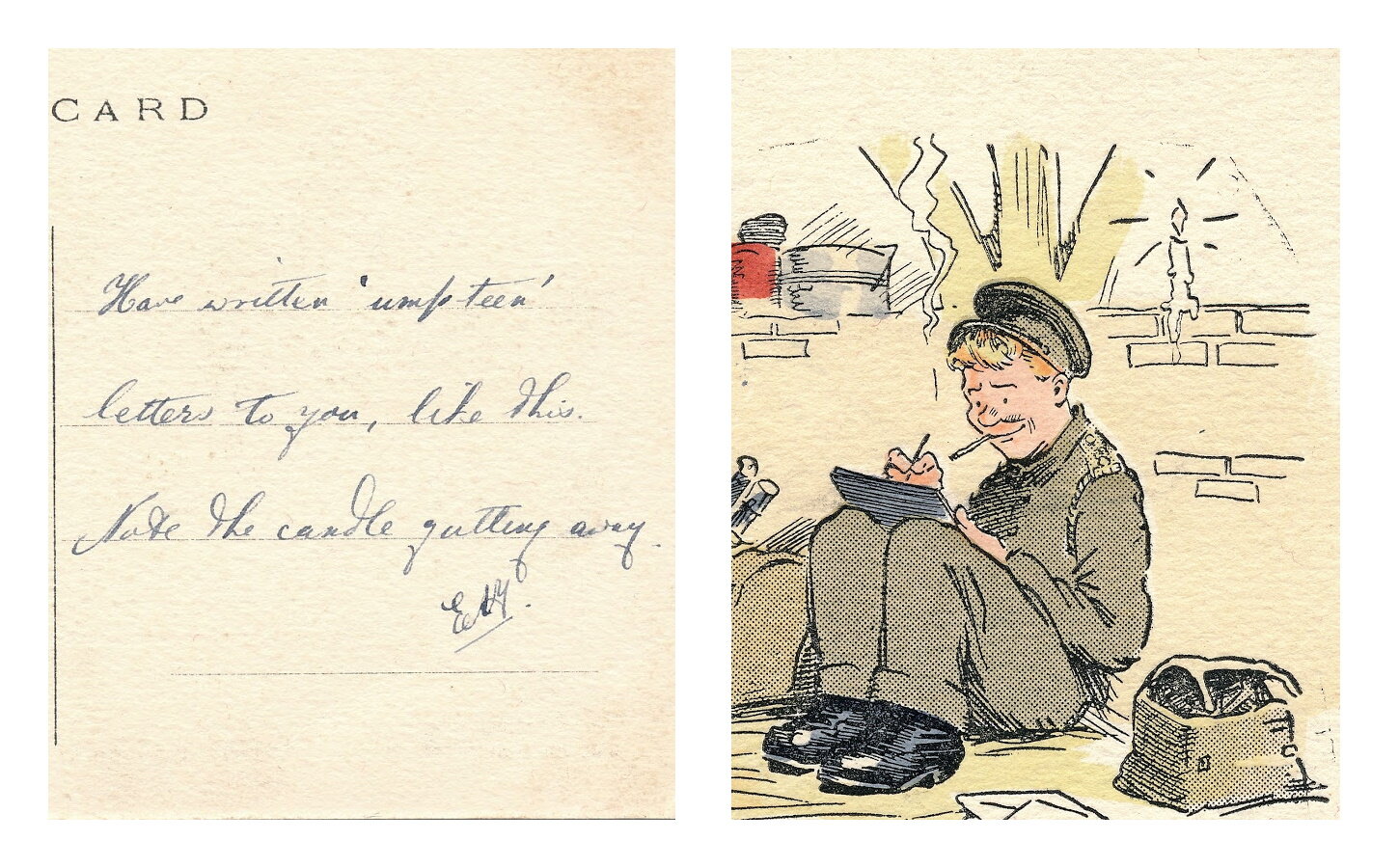

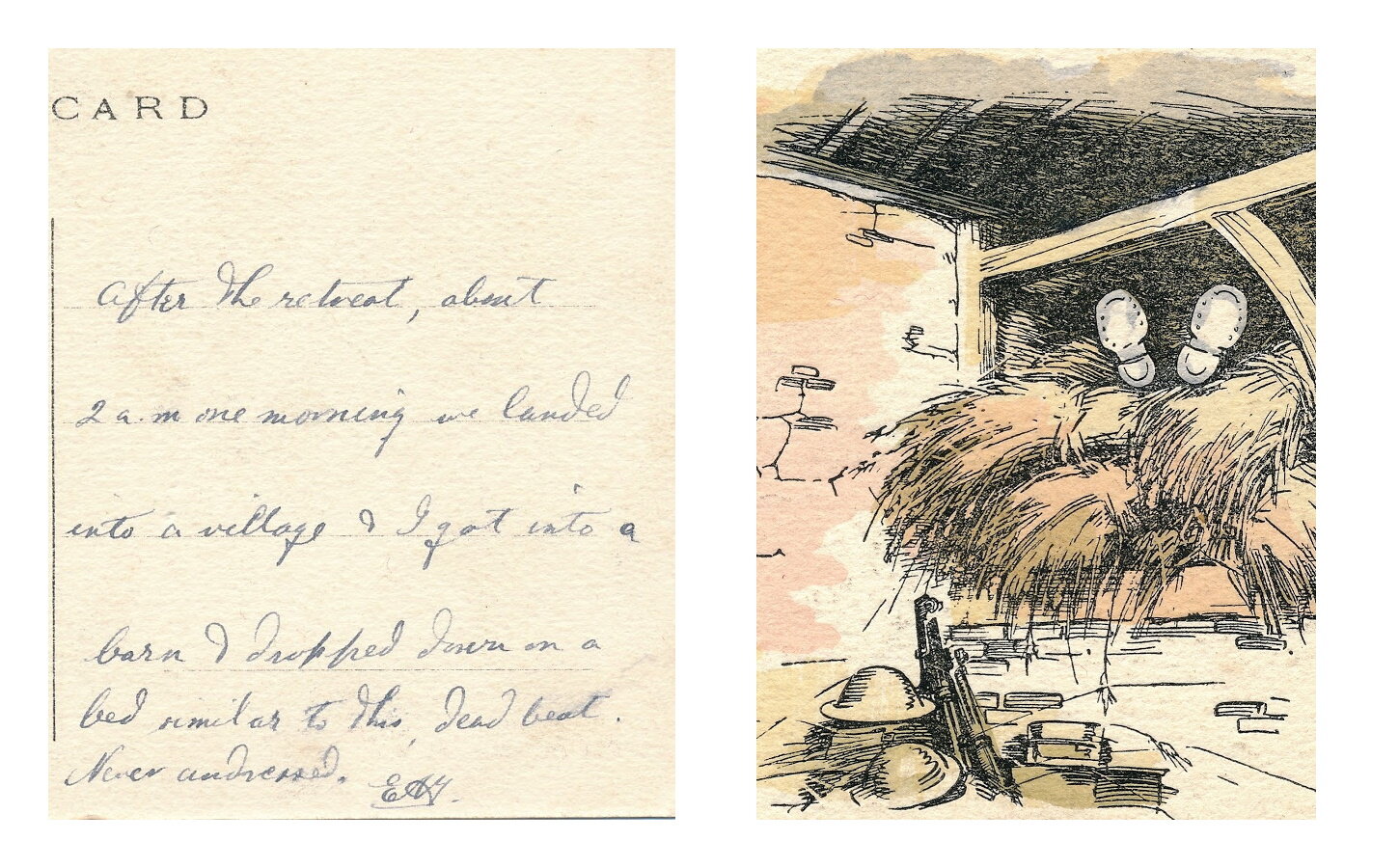

![“This is one of the truest pictures of life I have seen. It is not exagerated [sic] in the least”](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/522614d5e4b02f25c1dfd53c/1605418325335-YRQ556FT8TWNM6NN16GG/OOR5.jpg)