𝘠𝘐𝘐𝘒, or Why Impressions Matter in Storytelling

/Image courtesy of ACKK Studios

If you were part of the indie game scene in 2019, you’ve probably heard of YIIK. It was mocked extensively, declared the worst game ever made and was followed by endless controversy — both genuine and fabricated. (I recommend reading this interview with Andrew Allanson, the co-creator of YIIK. It sheds some light on a few controversies and gives insight on the making of YIIK.)

So it may come as a surprise that, in 2024, YIIK received a free, major overhaul (YIIK I.V), complete with a bundled-in sequel.

That begs the question:

Is YIIK good now?

I wouldn’t call it good, but I thoroughly enjoyed it — ironically and unironically. YIIK I.V is an intriguing experience that is worth giving a shot. The same cannot be said for its original release (YIIK 1.0), which, while not the worst game I’ve played, is up there.

But instead of reviewing YIIK I.V, I’d rather talk about why I think YIIK I.V achieved what YIIK 1.0 didn’t, story-wise. Because here’s the thing: Almost all of YIIK 1.0’s script remains in the overhaul. Most changes impact how the original script is interpreted, rather than changing the script itself.

(Side note: There’s no need to have played either iteration to understand this blog post, but there’ll be some minor spoilers.)

Reasons why YIIK I.V’s story reads better:

Additional content

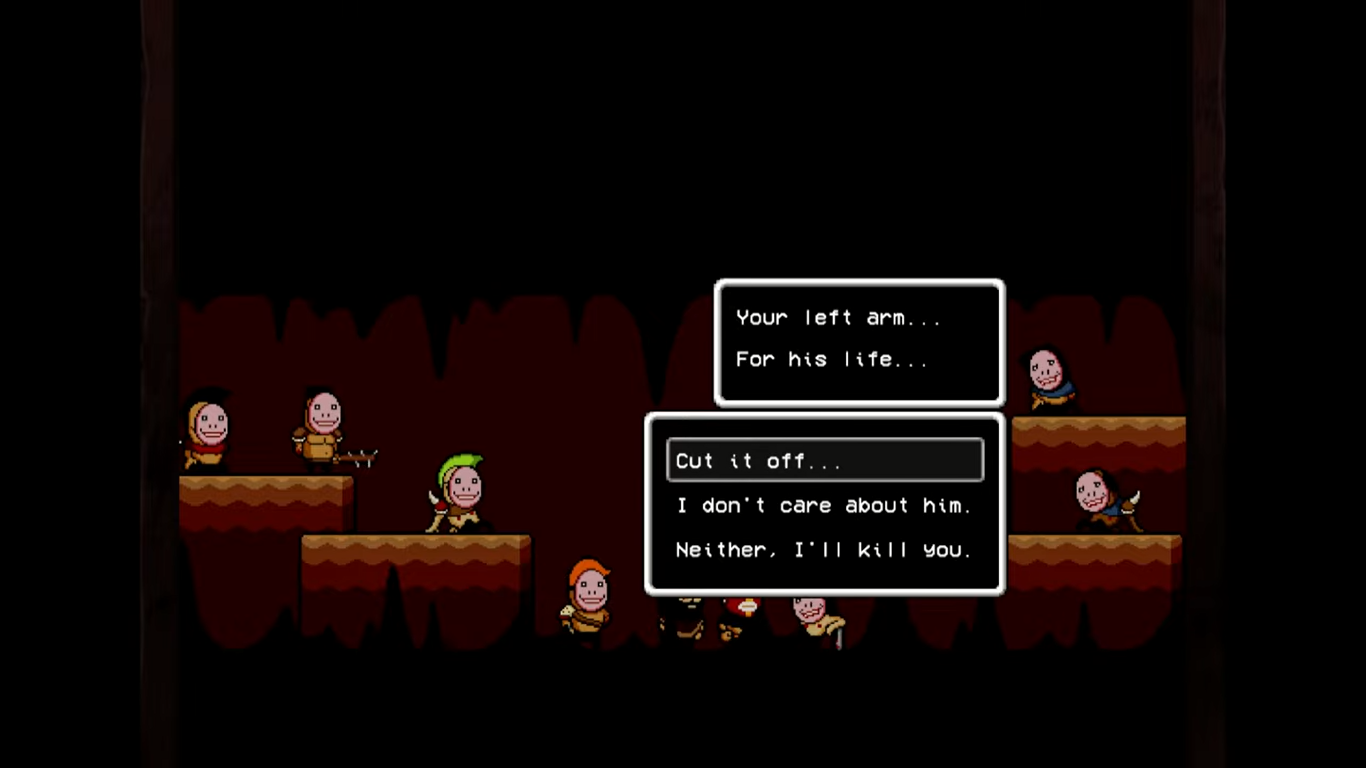

YIIK I.V adds lots of new content that supports the original script.

For an early example: YIIK 1.0 opens with a scene of Alex getting off a bus, which gives the false impression of a grounded story. YIIK I.V opens with an extremely surreal sequence of events — and then cuts to the bus scene. This better primes a player’s expectations; YIIK isn’t a grounded story that you should blindly accept as presented. Like a dream, it needs to be analyzed and interpreted.

It also makes it apparent that Alex is supposed to be unlikeable; in this sequence, before you even meet him, he is referred to as The Bad Brother.

Visual recontextualization

Many scenes have been visually changed to better communicate ideas to the player.

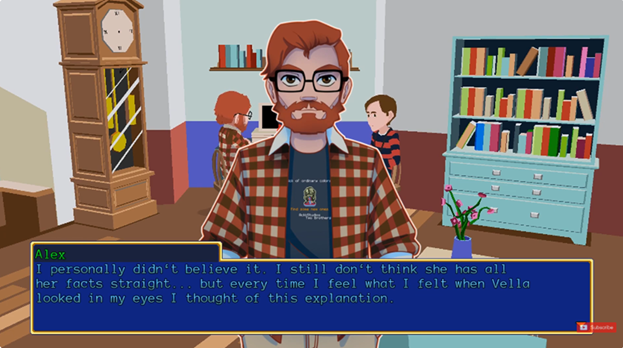

Take, for instance, Alex’s monologues:

Image courtesy of ACKK Studios

Image courtesy of ACKK Studios

Alex, a very unreliable narrator, monologues to the player throughout the game. By visually depicting these monologues as a performance in YIIK I.V, it clues the player to not take Alex at face value.

Gameplay fixes

YIIK 1.0 was a slow, buggy mess, complete with a combat system that could’ve been fun if it were executed with grace — and it was not.

It was glaringly sloppy.

YIIK’s story can be hard to grasp and a lot of things intentionally don’t add up. I think because the gameplay in YIIK 1.0 was so bad, people were conditioned into thinking deliberate decisions were mistakes.

For example: Alex states the year is 1999. In one conversation, Michael says that Lufia 2 is the holy grail of his youth, despite that game releasing in America in 1996. It was commonly believed that ACKK Studios didn’t bother looking this up.

But in that same conversation, Alex mentions Two Brothers, a game ACKK Studios released in 2013. Would they forget their own game was made over a decade later?

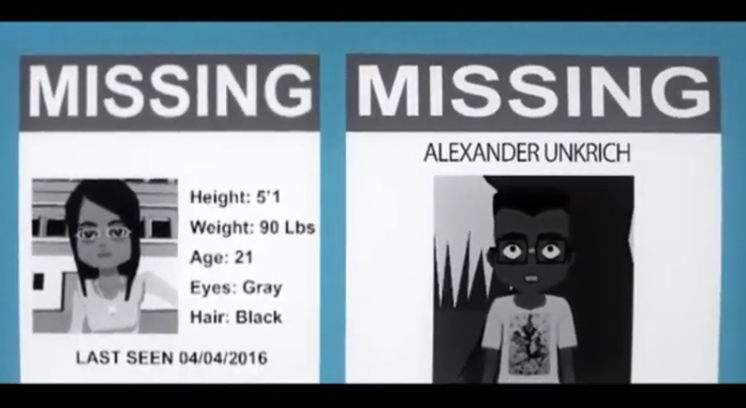

In YIIK I.V, the true year (2016) is shown before Alex ever claims it’s 1999 —

image courtesy of ACKK Studios.

The anachronisms were deliberate, because the game doesn’t take place in 1999. Andrew Allanson elaborates on why this is in his not-so-spoiler-free Discord post.

But when the gameplay gave such a bad impression, can you really blame people for assuming the writing must’ve been just as sloppy?

YIIK I.V’s gameplay is a far cry from YIIK 1.0’s. It is fun, functional, and full of flare. This, combined with its hard lean into surrealism, makes it harder for players to write off the story’s strange choices as ‘just another sloppy decision’.

The impression YIIK I.V couldn’t change

I mentioned the massive backlash YIIK got upon release. Such an infamous reputation makes people inclined to think poorly of YIIK, long before they ever play it. I sometimes wonder if I would’ve enjoyed YIIK more if I hadn’t heard of it beforehand.

It is unfortunate that YIIK was saddled with a reputation it only partially deserved. Despite the massive improvements in YIIK I.V, I doubt YIIK will ever escape that reputation. But we can at least learn one thing from YIIK: Impressions matter in storytelling.

(Photographed by Carol Wolf.)

The name is Mole Cricket. The world is a fascinating place when you’re cursed with sapience. I have too many thoughts in my mind and too much time on my claws. Without the need to work as my human peers must, I have endless time to devote to video games.

I first delved into the MOTHER series upon pupating, having heard of my kind’s inclusion in the series’ third instalment. It sparked my love for games and inspired many new gamedevs. My blog posts will examine games made by those devs over the decades.

I also graduated at the University of Texas with a masters in English. (The more impressive feat was not getting squashed by my squeamish classmates). You can follow me and my fellow bloggers here!