Sunrise on the Reaping: Written, then adapted, or written to be adapted?

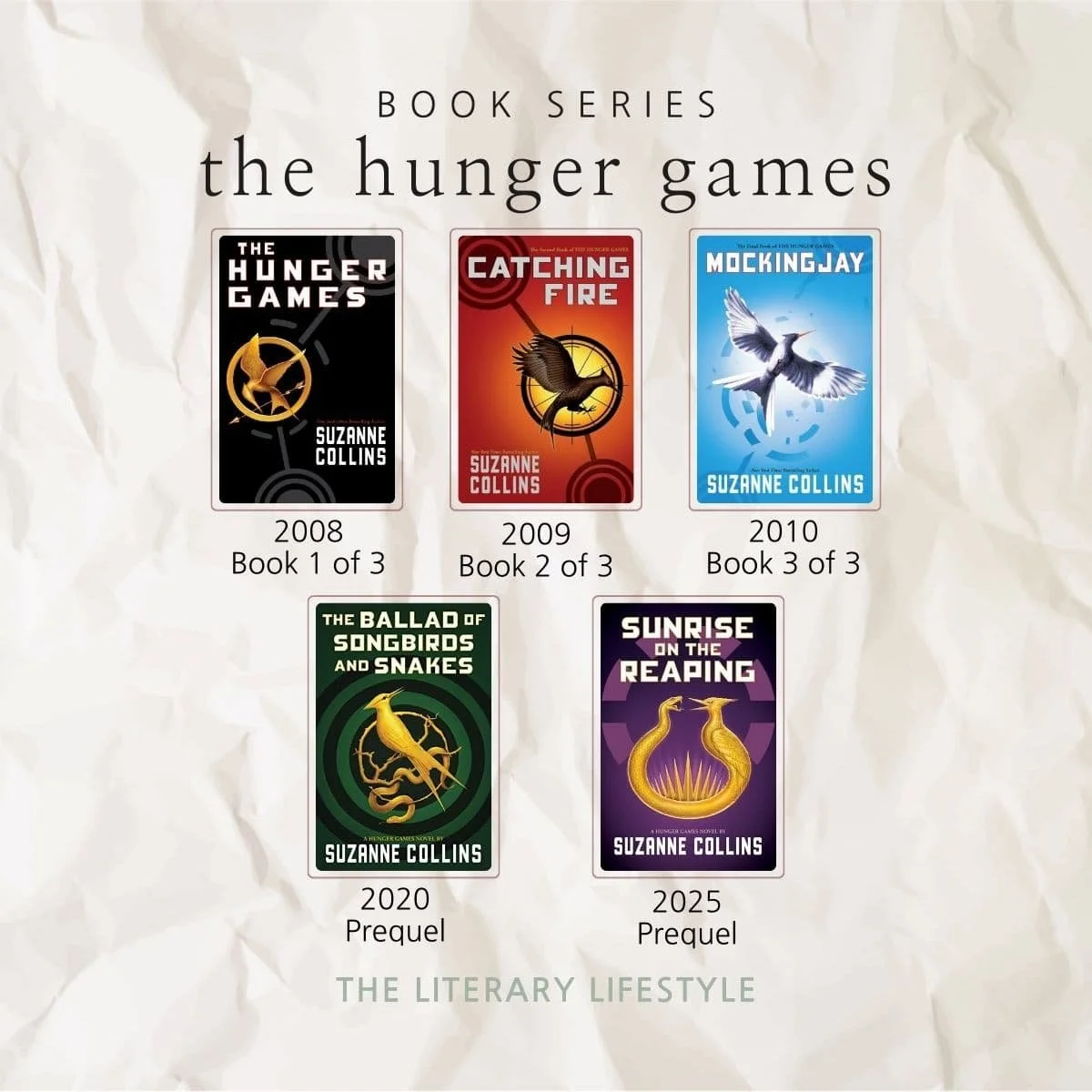

/The news that Suzanne Collins was writing another novel in the Hunger Games universe, Sunrise on the Reaping, was met with considerable excitement by fans, who were eager for more in the wake of Collins’ 2020 release The Ballad of Songbirds of Snakes. But there was another reason people were so excited about the announcement: not only was a book being published, it was already set to be adapted into a film.

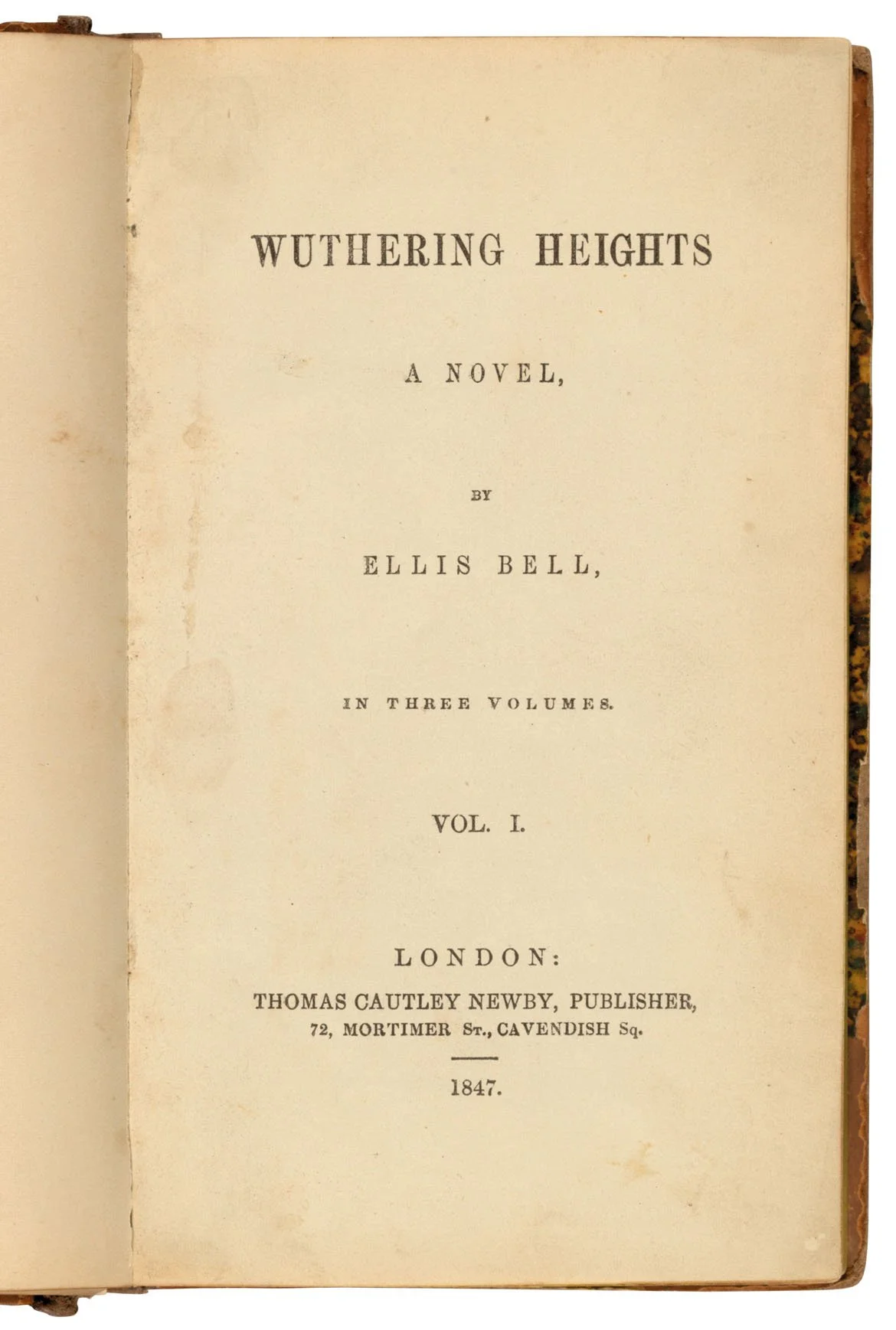

It’s highly unusual for an adaptation to be in production before the original work is even published; many books are decades-old by the time they get adapted. The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes was released more than three years before its own adaptation. And yet, The Hunger Games: Sunrise on the Reaping began casting its characters months before the novel was released. It seems clear that the novel was written with the goal of film adaptation in mind — after the commercial success of Songbirds and Snakes’ film adaptation, I have no doubt that publisher Scholastic and production company Lionsgate were eager to see a repeat.

Collins is a fantastic author, with brilliant characters and a thoughtful philosophical basis underlying every work; her Hunger Games series is bestselling and award-winning for a reason. Still, I find myself wondering just how much the writing in Sunrise on the Reaping was influenced by the expectation that it would be adapted. And, if it was, did that have a noticeable effect on the quality of the book?

Written, then adapted, or written to be adapted?

Sunrise on the Reaping follows a similar formula to the first and second books in the original Hunger Games trilogy: a reaping to select teenaged tributes from coal dust-covered District 12; a train journey to the glittering, technicolor Capitol; a whirlwind press tour-slash-training period; and a deadly battle in a camera-filled arena until only one tribute is left alive.

As in Catching Fire (the second novel in the original trilogy), the Hunger Games depicted in Sunrise on the Reaping is a “Quarter Quell,” a special installment of the annual Games which occurs every 25 years. Quarter Quells have higher stakes than the already deadly average Hunger Games, and the Reaping always has a twist — for this Games, the 50th, all twelve Districts are required to send four tributes, rather than the usual two. Among the tributes from District 12 is Haymitch Abernathy, who appears in the original trilogy as a mentor to the main characters before they take their turns in the arena.

For some, the arena, and descriptions of it, are a dead giveaway for the novel’s adaptation-based influence (can I coin that?). While the arenas in the original trilogy are well-described, from the deadly electric barrier to the manufactured acid rain to the bioengineered predators set on the tributes like lions at the Coliseum, Sunrise on the Reaping is especially descriptive, particularly when it comes to audiovisuals — exactly what a screenplay writer might want to have already laid out for them.

At the same time, many have noted that they found Sunrise on the Reaping noticeably more violent than previous installments in the series — which were considerably graphic and violent themselves — with some wondering whether this will make it more difficult to faithfully adapt into a PG-13 film. In addition, while a select number of characters are focused on in the novel, the story still comes with a significant cast — 48 tributes, plus Mentors, family members, Gamemakers, trainers, TV interviewers, politicians... It’s a lot of people.

Good or not good?

Clearly, people enjoyed Sunrise on the Reaping — it has a 4.51/5 star rating on Goodreads, and most major reviews were positive if not enthralled. If we ignore the debate over whether Goodreads ratings are a good basis for opinion, it’s pretty clear that people generally think the book was great.

But could it have been better? Well, yeah.

Haymitch isn’t the only character from the original trilogy to have a role in Sunrise on the Reaping. A frankly excessive number of characters from the original books appear, actually; many of the cameos range from pointless to contradictory. Even original main characters Katniss and Peeta have a role in the story. The blatant fanservice doesn’t necessarily mean anything movie-wise, it is an easy way to encourage audience engagement and interest in both the book and the movie.

Then there’s the matter of redundancy: the book has no real purpose, and no impact on the other works in Collins’ catalogue. It follows the same formula and, to a large extent, the same characters as the original books. And despite its lack of impact, it can’t stand on its own, either; it’s too entrenched in the overall story.

As many a comment reviewer online has said — combine the fanservice and excess cameos with the redundancy of the book itself, and, well, it reads a lot like fanfiction.

It’s difficult not to wonder if this book wasn’t just influenced by its “soon to be a major motion picture” status, but in fact only written because of it in the first place. Did Collins even want to write this book — or at least to write it the way she did — or was she voluntold by her publisher? It’s not a bad book, but it doesn’t have the originality, subterfuge, and suspense that we usually see from Collins’ Hunger Games installments. It’s good, no doubt, but it’s not as good as it could have been.

What’s next?

As soon as Sunrise on the Reaping was announced, Hunger Games fans were already discussing whether there would be another new book, and who it might focus on. Many online seem to think — or at least hope — that Collins’ next installment will focus on Finnick Odair, a skilled tribute in Catching Fire who was exploited following his victory in his first Games. Others think that focusing on Finnick would be too much fan service — but if it’s happened once, why can’t it happen again?

If there are future installments, they, too, will almost certainly come with a film deal attached. And while that’s not necessarily a bad thing, and Suzanne Collins isn’t a bad writer, I still worry that another novel like this will be too much of a not-so-good thing. Whatever Collins writes next will definitely be thrilling, engaging, and thoughtful — but how original it is? I guess we’ll have to wait and see.

Moira Rickett is a freelance editor and translator and a student in the Professional Writing program at Algonquin College. She likes nonfiction writing, literary analysis, and collecting useless trivia, usually about dead historical figures. When not working on her latest project, she can usually be found procrastinating working on her latest project.